M2.03. Analysing the conditions relevant to the mentoring process at the workplace

M2_MU_03. Analysing the conditions relevant to the mentoring process at the workplace

| Strona: | EcoMentor Blended Learning VET Course |

| Kurs: | Course for mentor in the sector of eco-industry |

| Książka: | M2.03. Analysing the conditions relevant to the mentoring process at the workplace |

| Wydrukowane przez użytkownika: | Gość |

| Data: | piątek, 31 października 2025, 15:07 |

Spis treści

- 1. What is the “corporate culture”

- 2. Uncover problems regarding the learner’s job satisfaction or mentoring process thanks to inputs from the mentee

- 3. Organisational policies and procedures relevant to the mentoring process

- 4. Operational context of the employing organisation and working methods

- 5. Resources and relevant personnel of the employing organisation

- 6. Pitfalls and barriers affecting the mentoring process in the workplace

- 7. Problems and causes affecting the mentoring process and possible solutions

- 8. Bibliography

1. What is the “corporate culture”

Creating a Corporate Culture

Values and Ethics. Whatever it is that a company states is its driving force – what it values – will affect what its employees focus on. The culture of a company that values caring will be different from one that values, say, creativity or speed or precision. One isn’t necessarily better than another; it simply will impact the types of employees that are hired and what everyone is working toward.

Employees. To build a corporate culture that matches what leaders want the business to be known for, you have to hire carefully. Each and every employee needs to match the culture and the company’s values. Companies with the most desirable corporate cultures invest a lot of time recruiting and interviewing potential new hires because they recognize how essential each person is to supporting the culture.

Work Environment. Where employees have to work will have a major impact on the organization’s culture. Pack everyone in a tight space like sardines, with little light and few creature comforts and you will likely build a culture centred on negativity and complaints. Whereas a space that is open and airy, with ample workspace, will foster positive feelings and lower stress. Workspace matters.

Actions. How a company demonstrates its values and priorities also shapes its corporate culture. Do its actions align with its values, or not? Companies that put customer satisfaction as its highest priority should have processes and procedures that ensure customers are delighted with its dealings with the company. Satisfaction guarantees, no hassle refunds, and no expiration dates on returns could be policies that support such a value.

Opportunities for bonding. Companies that set aside time outside of work to socialize and get to know each other create opportunities for more fulfilling personal relationships to form. Some companies have annual off-site meetings that bring together all employees to talk about what’s going well and what’s not. Other companies schedule more frequent, and less formal, get-togethers, such as softball teams, potluck dinners, and Friday cocktail hour.

How employees feel about, and express satisfaction with, their employer is the basis of a corporate culture. The more positive and fulfilled employees are with the organization they work for, the more loyal and effective they will be. That’s the benefit of a positive corporate culture.

Look at this video by S+B Strategy+Business to know more about “What Is Corporate Culture?”

2. Uncover problems regarding the learner’s job satisfaction or mentoring process thanks to inputs from the mentee

Putting the mentee first: An effective mentoring programme ensures that it fully understands the circumstances and specific needs of its clients and delivers a service which is geared to serving their best interests and supporting their individual progress. A statement of the values will signal commitment to providing a service which reflects the mission and vision of the programme and which demonstrates good practice. For example, we aim to:

- provide structured and supported relationships that meet the needs of the mentee and the mentor;

- promote caring and supportive relationships;

- encourage individuals to develop to their fullest potential;

- help individuals develop their own vision for the future.

The mentoring relationship is a special relationship where two people make a real connection with each other. In other words they form a bond. It is built on mutual trust and respect, openness and honesty where each party can be themselves. It is a powerful and emotional relationship. The mentoring relationship enables the mentee to learn and grow in a safe and protected environment.

As a Mentor, it can be very easy to want to just jump in and solve Mentee’s problems for him/her. However, Mentor’s role is to help the Mentee think for him/herself, and to do so, this involves asking thought-provoking questions in order to help Mentee to reflect on his/her experiences and learn from Mentor’s ones. Dialogue between Mentor and Mentee is an opportunity to:

- Uncover additional facts and information about the mentee;

- Confirm mentee’s goals, aspirations, and needs;

- Explore strong feeling about situations;

- Define problems and possible solutions;

- Discover mentee’s commitment to his/her growth.

Monitoring is conducted on an on-going basis as a health check, allowing for early intervention when things go off-plan or to alter aspects of the programme in light of experience. Mentors and mentees should be primary contributors to the process of monitoring and to the final evaluation. Asking them what they found most useful and what they feel needs to change will empower participants and provide valuable evidence about their experience of mentoring. Methods of gathering monitoring data can include:

- scheduled meetings with mentors and mentees;

- methods for collecting on-going feedback (suggestion boxes, mentor supervision sessions);

- written records e.g. meeting logs, action plans which track the mentee’s journey;

- evidence from support and or supervision sessions with mentors;

The evaluation process should be based on an outcome analysis of the programme and of the mentoring relationships.

Suggested methods of gathering evaluation data:

- interviews or feedback sessions (singly or as groups) with mentors, mentees and line managers at appropriate intervals;

- include exit interviews;

- focus groups;

- self-report questionnaires from mentors and mentees. Decide how often this is done. This will depend to some extent on the duration of the mentoring activity;

- assessment of achieved and missed milestones, goals and outcomes which are identified and recorded through action planning processes against desired outcomes.

3. Organisational policies and procedures relevant to the mentoring process

The mentoring program should have formal policies, procedures, and responsibilities in place to ensure the purpose and goals are met. At a minimum, policies and procedures should be established for the following aspects:

- Duration of the mentoring relationships (i.e., 6 months, 1 year, etc.);

- Matching rules (mentees to mentors);

- Roles and responsibilities for program manager, mentors, mentees and other stakeholders;

- Whether participation in mentoring program group activities is mandatory or optional;

- Dealing with a Mentee-Mentor Mismatch;

- Closure (of the mentoring relationships).

- Providing documentation of the organization’s vision and operating principles. A policy and procedure manual provides a clear statement of the program’s mission, values, and vision and provides the framework that defines the mentoring program’s operating principles and processes.

- Providing staff with clear guidelines on how to administer a program. A policy and procedure manual provides detailed, step-by-step instructions on how to administer the mentoring program and clearly defines staff roles, company’s expectations, and routine operating guidelines.

- Addressing risk management issues. A policy and procedure manual is the cornerstone of the risk management plan because it provides clear and explicit instructions on how every part of your mentoring program will be administered. Developing a policy and procedure manual will help eliminate uncertainties concerning how to safely, effectively, and consistently run the mentoring program.

- Ensuring consistent operations despite possible turnover in key staff. If policies and procedures are not documented, the organization risks losing crucial program operations knowledge if a key staff member leaves. By clearly detailing, in writing, how the mentoring program is run, it’s possible to minimize organizational knowledge loss and program disruption. A policy and procedure manual will help the program to maintain continuity of services and will assist the mentor in training new staff members.

- Serving as a blueprint for program replication and expansion. A policy and procedure manual gives a consistent model for program expansion or replication.

- Serving as a baseline for continuous improvement. Although developing the policy and procedure manual is hard work, this important task forces the organisation to examine its mentoring program and be honest about the structure of current program practices. Once written, the policy and procedure manual provides a concrete starting point that will allow continually improving and refining the mentoring program.

Policies

Policies are high-level program statements that embrace the goals of mentoring program and define what is acceptable to ensure program success and effective and consistent program operations. Policies are crucial to the mentoring program achieving its goals and are mostly developed for program practices that are mandatory and non-negotiable in nature. For example, a policy might address the level of screening all mentors must complete or whether your program allows interactions outside the context and working hours between mentors and mentees. Policies are typically approved and monitored by a board inside the human resource department of the company.

Procedures

Procedures are statements that describe how a particular operational function is implemented and managed within the mentoring program. Procedures are brief statements that describe the step-by-step process necessary to implement policies and other organisation’s practices. Procedures often include who should carry out tasks and when those tasks are to be done. Examples of mentoring program procedures include the process for conducting background checks, the steps staff follow when matching a mentor and mentee, and the sequential process for closing a match between the mentor and mentee. Procedures are usually governed by the mentoring program coordinator or other staff but may also require executive director and/or board approval.

4. Operational context of the employing organisation and working methods

There is no one perfect model for every organisation. When designing a mentoring program it’s important to keep in mind and identify the main aspects of the employing organisation.

1. Goals. Are you developing tomorrow’s leaders? Or working on educating employees about certain procedures? Identify your key objectives.

2. Desired outcomes. What do you want the results to be? Improved performance now? Longer-term management skill development?

3. The methods to achieve the outcomes. For skills training, a month-long coaching program may be the method. For succession planning, perhaps a longer mentoring type of program will work better.

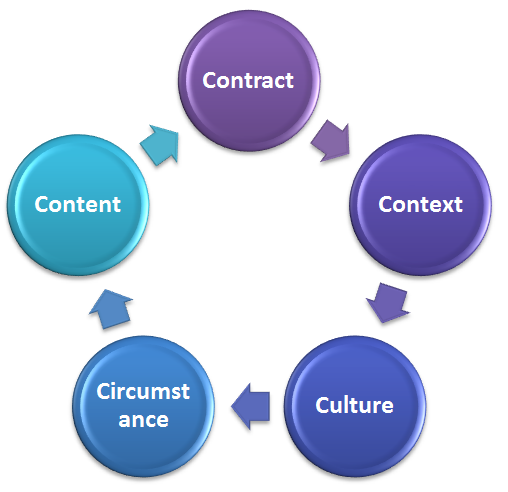

When deciding to employ mentoring please remember to consider the “Five Cs”:

Five Cs (free elaboration)

2. Context: What are the business objectives to be fulfilled by the program? Stage of career development, succession planning, etc.

3. Culture: How credible are coaching and mentoring within the culture? Are senior executives available to serve as mentors? Do you have senior level support for your program?

4. Circumstance: What sort of budget does the organization have for talent development? Can the objectives just be outsourced to external coaches?

5. Content: What subject matter will be discussed within the mentoring relationships? Understanding the possible content will help determine the type of developmental dialogue to employ.

Identifying these parameters up front will help point you to the types of coaching and mentoring programs that will work for the employing organization.

Working methods

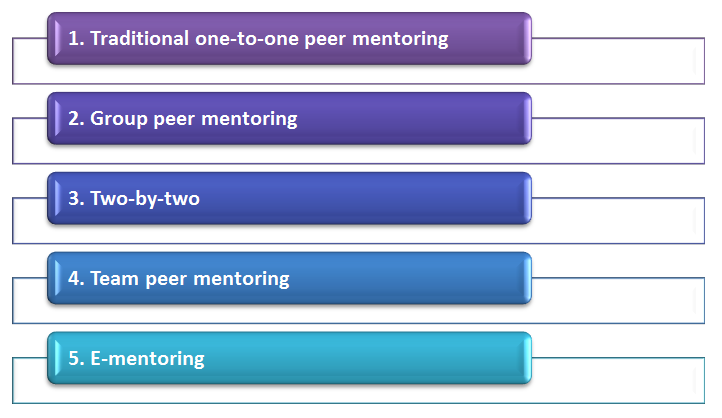

Although mentoring arrangements traditionally refer to a partnership between two people, other models have been developed over time reflecting the changing priorities and practices of the workplace. Responses to challenges such as capacity building, leadership development and quality improvement have led to the creation of a range of more creative approaches to mentoring. The following five models can provide a starting point. They are by no means exhaustive and can be adapted and evolved to suit other contexts and circumstances with two or more models operating within a single mentoring programme.

The five models are:

1. traditional one-to-one peer mentoring (one mentor/one mentee);

2. group peer mentoring (one mentor/one to four mentees);

3. two-by-two (two mentors/two mentees);

4. team peer mentoring (one or two experienced mentors from out with the team working with a group of mentees in the same work team);

5. E-mentoring.

2. Five Mentoring Models (free elaboration)

2. Group peer mentoring (one mentor/one to four mentees): A group of mentees meet regularly over a designated period of time, with the support of an experienced mentor. This type of mentoring can offer colleagues who lead a team and who may feel isolated, an opportunity to work together with peers on shared challenges and potential areas for development and growth. If there is a shortage of mentors within or across organisations, a mentor may work with several mentees, meeting with them as a group. This may also be the model of choice. It has the added bonus of allowing the mentor as well as the mentees to benefit from a wider pool of knowledge and experience. We recommend that mentors offer one-to-one sessions out with the group setting if requested.

3. Two-by-two (two mentors/two mentees): This model can provide opportunities for new mentors to work alongside someone with more experience in the role whilst offering mentees the option of one-to-one sessions with a mentor. It is also beneficial for mentees as they have a wider pool of skills and knowledge on which to draw.

4. Team peer mentoring (one or two experienced mentors from out with the team working with a group of mentees in the same work team): Team peer mentoring can involve a diverse group including experienced, well-established people as well as newcomers to the team. Newcomers will have the added benefit of ready access to networks that will offer support, important information, and contacts. A team environment with the same goals and objectives is ideal for mentoring. Members can support and help one another, ultimately making the entire team stronger. This is an opportunity for the mentors who provide this service to develop and demonstrate their leadership skills.

5. E-mentoring: In these times of increasing technological change and electronic communication, it is not surprising that web-based technology is being used to assist with mentoring and mentoring programs. E-mentoring relies on computer-mediated communication (CMC) such as email and other electronic communication technologies to enable the mentoring to take place.

5. Resources and relevant personnel of the employing organisation

Mentoring can improve employee satisfaction and retention, enrich new-employee initiation, make the company more appealing to recruits, and train the leaders. And the best part is that it's free. Unlike similar learning incentives like training programs or offering to pay for courses, mentoring utilizes the resources that the company already has.

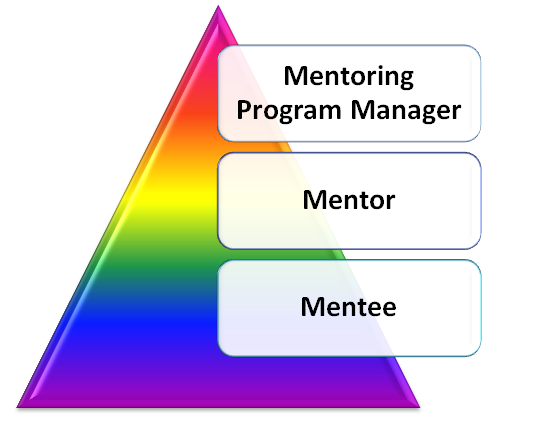

The relevant personnel involved in the mentoring process are:

1. HR Manager that works also as Mentoring Program Manager: he/she oversees development, implementation and evaluation of the mentoring program; together with the mentor and the mentee he/she defines goals and objectives for the Individual Mentoring Program (IMP);

2. Mentor: he/she works with the mentee in developing and implementing an Individual Development Plan (IDP), ensures mentee work projects have start and end dates, and do not distract from the mentee’s official duties, meets routinely with the mentee to discuss and monitor progress, provides feedback and recommendations for program improvement;

3. Mentee: he/she meets routinely with mentor, actively participates in mentoring activities and goal accomplishment, and provides feedback and recommendations for program improvement.

The following documents need to be developed and provided to support a smooth process for potential mentees and mentors, to evaluate and continuously improve the mentoring program:

- Applications (for mentees and mentors)

- Confidentiality Agreement

- Mentoring Agreement

- Mentee Action Plan

- Mentoring Log

- Evaluation Forms

Confidentiality Agreement: The mentoring program must be a safe environment for mentees and mentors to freely share information about one another. To help build trust, they must be able to establish clear boundaries on how the shared information is to be treated.

Mentoring Agreement: The mentoring agreement establishes how and when the mentee and mentor will meet.

Mentee Action Plan: To determine activities to ensure mentoring goals are met, a mentee action plan is a must. The mentee will complete the plan with help from the mentor.

Mentoring Log: The mentee and mentor should record their meetings and activities to show progress achieved and assist with end-of-program feedback.

Evaluation Forms: At the mid-point of the program and at the end, you must ask the mentees and mentors to evaluate the program. Their input will help you make any necessary adjustments to ensure the program remains effective.

It could be also useful to establish a library of materials and resources to assist mentors and mentees during the program. Examples include how-to guides, job aids, and recommended reading materials and websites.

6. Pitfalls and barriers affecting the mentoring process in the workplace

Pitfall 1: Mentoring without a clearly identified purpose

Relationships will fail if there is no clearly defined and agreed purpose. Meetings will have little or no structure, can stray easily into territory out of the boundaries of mentoring practice, will waste time and will be difficult to review, monitor and evaluate effectively.

Pitfall 2: Having no defined end point

Without timescales the relationship is likely to drift aimlessly. Having an end point makes it easier to set goals. However, this does not mean that timescales cannot be reassessed in light of developments. It can also influence how often you hold meetings.

Pitfall 3: Irregular meetings and postponing meetings regularly

Both parties are busy people who will not always be in a position to change arrangements at the last minute. Knowing in advance when the meeting will be held allows the mentor and mentee to schedule their week and more readily set their objectives and prepare for their meetings.

Pitfall 4: Not knowing how to structure meetings and how to begin the process

It is important that there is an agenda for each meeting. Identifying and setting goals at the beginning of the relationship, which you can explore in more depth as meetings progress, is also crucial.

Pitfall 5: No, or inadequate, preparation for closure or ending of the relationship

Both parties need to prepare for the end of the relationship. Taking the time to discuss and acknowledge that it will not go on forever and having an idea about when it will end as a formal arrangement, will go some way towards avoiding dependency and feelings of loss. When you reach the end point the relationship may end completely or continue on a different basis: different timeline, different goals.

Pitfall 6: Confusion of roles - coach or counsellor

There is common confusion about the role of the mentor, for example sliding into the role of counsellor. Having a role description with clearly stated objectives and the opportunity to participate in a robust training session will provide opportunities to explore the role and its boundaries and to consider additional sources of support and guidance for issues which may arise.

Pitfall 7: Lack of mentoring experience - believing that being an effective manager or supervisor is a good predictor of mentoring success

The credentials for mentoring are not necessarily within the skillset of successful managers or supervisors. Mentoring is a skill, like all others, which improves with training, reflection, practice and experience.

Pitfall 8: Mentor as line manager

Many organisations appoint line managers as mentors. This rarely works. The role of manager is generally seen to be incompatible with the mentor role as both have different aims and objectives in their relationship with the mentee/employee - the mentor focuses on the mentee and the manager focuses on the work and the organisation.

Pitfall 9: Failure to review progress and the effectiveness of the relationship

Mentors and mentees should build in a regular review of the relationship and the progress they are making. Failure to do this can reduce the chances of achieving the goals which have been set – goals and actions need to adapt and in some instances change as things progress. If you do not monitor and review the quality of the relationship regularly and with honesty, problems may go unrecognised or acknowledged causing, in some instances, irreparable damage to the relationship.

7. Problems and causes affecting the mentoring process and possible solutions

|

Problem |

Possible cause |

Possible solution |

|

Managers use mentoring to deal with poor performers |

Don’t understand program goals, avoiding alternate action |

Discuss program goals, role of mentor versus supervisor |

|

Time-management issues |

Program is placing unrealistic demands on participants, lack of commitment, program not an integral part of the human resource strategy, orientation and training takes too long |

Review program expectations Review HR strategy and the place of mentoring in this. |

|

Lack of immediate visible result |

Unrealistic expectations, Not enough time available for participants to work on relationships and goals |

Allow reasonable time before judging outcomes, provide time for participants to allocate to the relationship |

|

Few people want to participate as mentors or mentees |

Inadequate advertising and promotion, lack of support for participants, too many other work pressures |

Review communications strategy, Clarify goals Provide adequate resources |

|

Unsuccessful matching |

Personality clash, difference in styles or standards, poor selection and or matching |

Review selection and matching procedures, allow no fault divorce |

|

Discontent among nonparticipants |

Jealousy for not being selected, misunderstanding of program goals |

Increase opportunities for appropriate matchings, promote program goals more widely |

|

Mentoring partnerships not operating according to guidelines e.g. not taking their role seriously, failing to provide or accept feedback, one party taking credit for the other’s work, the mentor using the mentee as member of staff |

Role expectations not clearly established, poor training, inappropriate selection |

Renegotiate expectations, provide adequate training, renegotiate partner |

8. Bibliography

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/corporate-culture.asp#ixzz5BgpGHErF

- https://www.strategy-business.com/

- Lacey, K. (1999). Making mentoring happen: a simple and effective guide to implementing a successful mentoring program. Warriewood, NSW: Business & Professional Publishing Pty Ltd.

- University of Glasgow. Mentoring scheme best practice https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/humanresources/employeeandorganisationaldevelopment/developmentaltoolkits/mentoringtoolkit/

- CIPD - Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (London) West Yorkshire CIPD, Branch Mentoring Programme https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/west-yorkshire-mentoring-pack_2011_tcm18-9423.pdf

- The Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) 2014, Mentoring: Supporting and Promoting Professional Development and Learning, www.sssc.uk.com http://www.stepintoleadership.info/assets/pdf/SSSC%20Mentoring%20guidance.pdf

- McKimm J., Jollie C. and Hatter M. (2003). Mentoring: Theory and Practice http://www.faculty.londondeanery.ac.uk/e-learning/feedback/files/Mentoring_Theory_and_Practice.pdf

- Ballasy L., Fullop M., Garringer M.: Effective Strategies for Providing Quality Youth Mentoring in Schools and Communities, Generic Mentoring Program Policy and Procedure Manual, Hamilton Fish Institute (Washington, DC 20037) http://www.hamfish.org http://www.mentoring.org/images/uploads/MentoringPolicy.pdf

- WHITE PAPER - HOW COACHING & MENTORING CAN DRIVE SUCCESS IN YOUR ORGANIZATION by Lis Merrick - Managing Director, Coach Mentoring U.K., for Chronus Corporation https://hru.gov/documents/MentoringStudio/How%20Coaching%20%20Mentoring%20Can%20Drive%20Success%20in%20Your%20Organization.pdf

- Developing Performance Mentoring Handbook, Department of Education, Training and Employment by Dr Lisa Catherine Ehrich, Queensland University of Technology, September 2013 http://education.qld.gov.au/staff/development/performance/pdfs/dp-mentoring-handbook.pdf