M2.04 Conducting the mentoring process

M2_MU_04 Conducting the mentoring process

| Strona: | EcoMentor Blended Learning VET Course |

| Kurs: | Course for mentor in the sector of eco-industry |

| Książka: | M2.04 Conducting the mentoring process |

| Wydrukowane przez użytkownika: | Gość |

| Data: | niedziela, 19 października 2025, 20:13 |

Spis treści

- 1. Use mentoring techniques and methods for achieving learner’s learning outcomes and goals

- 2. Mentoring using the GROW model

- 3. How individuals learn

- 4. Work with learner to undertake the learning

- 5. Ensure that the learner has an adequate support by workplace management and colleagues for learning

- 6. Mentoring to support successful work‐based learning programmes

- 7. Conflict during the mentoring process

- 8. Conflict Styles

- 9. Conflict resolution theory, methods and models that can be used during the mentoring process

- 10. Bibliography

1. Use mentoring techniques and methods for achieving learner’s learning outcomes and goals

Mentoring can be used for a wide variety of situations and different points in someone’s working life for example:

- Induction for a new starter;

- Individuals working towards promotion;

- Staff who have changed roles in the department or across the organisation;

- Staff on structured learning programmes;

- Changes to job roles for example following a restructure;

- Continuous Professional Development (CPD).

There are different ways a Mentee can be supported, encouraged and given constructive feedback. With each technique, it is important to be aware of its purpose, appropriateness, the likely impact and its value to the Mentee.

Techniques can include:

Techniques can include:

- Giving advice – offering the Mentee your opinion on the best course of action;

- Giving information – giving information on a specific situation (e.g. contact for resource);

- Taking action in support – doing something on the Mentee’s behalf;

- Observing and giving feedback – work shadowing and observation by either or both parties. Observation coupled with constructive feedback is a powerful learning tool;

- Reviewing – reflection on experience can develop understanding allowing one to consider future needs, explore options and strategies.

The selection of techniques can be guided by a number of factors, such as:

- Values and principles underpinning the Mentoring scheme – in this case, encouraging self-sufficiency and empowerment;

- Shared understanding between Mentee and Mentor of the purpose behind the Mentoring relationship;

- Quality and level of the professional relationship;

- Level of experience and need of the Mentee;

- Level of Mentor’s own awareness and comfort with the Mentoring process.

Mentoring is an empowering experience for the Mentee; it is therefore vital that the strategies chosen encourage the Mentee towards autonomy. The Mentee is expected to negotiate the forms of support needed at the initial contracting stage; by making use of processes that are self-helping such as learning logs, self-review journals, reviewing meetings and feedback. The relationship can be used to develop skills for both parties and is dependent on clear communication. This all-important communication can benefit from analysing a number of key skills, active listening and questioning.

The skill of Active Listening

Active listening is the ability to listen and internalise what is being said; essentially listening and understanding. You can use your whole self to convey the message of an active listener involved in the discussion, showing interest, gaining trust and respect.

This can be achieved by using verbal and non-verbal communication. Non-verbal communication has more impact than words alone, so facial expression, eye contact, non-verbal prompts (e.g. head nodding) and body posture (leaning slightly towards the Mentee, showing interest) will contribute towards building upon the professional relationship and improving discussions.

Your surroundings can also be utilised to create a climate appropriate for discussion to occur. The aim is for a quiet, pleasant and relaxed environment with no physical barriers (e.g. a desk between Mentor and Mentee) to be used to conduct the meeting in.

Using the art of questioning

Questioning, if used effectively, is a very useful and powerful tool. It allows the Mentee-Mentor relationship to develop, assisting the Mentor in understand the Mentee’s situation or dilemma, assisting the Mentee in exploring and understanding their experiences with the hope of formulating avenues and actions for the future. There are many reasons to ask questions, they may be:

The skill of Active Listening

Active listening is the ability to listen and internalise what is being said; essentially listening and understanding. You can use your whole self to convey the message of an active listener involved in the discussion, showing interest, gaining trust and respect.

This can be achieved by using verbal and non-verbal communication. Non-verbal communication has more impact than words alone, so facial expression, eye contact, non-verbal prompts (e.g. head nodding) and body posture (leaning slightly towards the Mentee, showing interest) will contribute towards building upon the professional relationship and improving discussions.

Your surroundings can also be utilised to create a climate appropriate for discussion to occur. The aim is for a quiet, pleasant and relaxed environment with no physical barriers (e.g. a desk between Mentor and Mentee) to be used to conduct the meeting in.

Using the art of questioning

Questioning, if used effectively, is a very useful and powerful tool. It allows the Mentee-Mentor relationship to develop, assisting the Mentor in understand the Mentee’s situation or dilemma, assisting the Mentee in exploring and understanding their experiences with the hope of formulating avenues and actions for the future. There are many reasons to ask questions, they may be:

- To satisfy curiosity

- To obtain or clarify information

- To assist in exploring an issue

- To look at possible alternatives

- To check understanding

- To challenge contradictions, views etc.

- To move the discussion forward

- To direct the discussion

With the effect questions have and their power, it is important to select those which are of greatest use. Questions can essentially be broken down into two types, closed or open questions.

Open Questions: These are questions which require more than just a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response and usually begin with ‘How?’ ‘Where?’ ‘What?’ ‘Who?’. Questions beginning with these can be used to:

Open Questions: These are questions which require more than just a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response and usually begin with ‘How?’ ‘Where?’ ‘What?’ ‘Who?’. Questions beginning with these can be used to:

- Gain information – ‘What happened as a result of…?’

- Explore personal issues – ‘What is your view on…?’ ‘What are you expecting to achieve?’ ‘How are you feeling having...?’

- Consider and explore avenues – ‘What are the possible options for...?’ ‘What may help when...?’ ‘How would you deal with...?’

Closed Questions: These are questions which evoke a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response and in doing so narrow down the opportunity for the Mentee to expand, closing down the discussion e.g. ‘Do you…?’; ‘Did you…?’. Continual use of closed questions will restrict the discussion, resulting in the Mentee saying less and the Mentor asking more and more questions. The overall effect is poor communication and a difficult environment to work within. There are times when closed questions are useful. They can be used to summarise and confirm a discussion, bringing parties up to speed and to the same level e.g. ‘So, you are saying that you don’t have an issue with...?’.

Avoid asking multiple questions. These are a number of different questions asked within the same sentence. They are unclear, cause confusion and stop both parties from focusing on the meeting.

Avoid asking multiple questions. These are a number of different questions asked within the same sentence. They are unclear, cause confusion and stop both parties from focusing on the meeting.

2. Mentoring using the GROW model

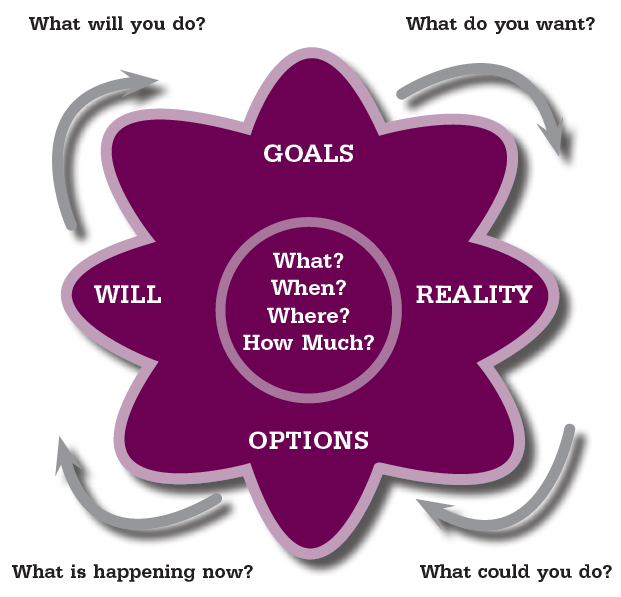

The GROW model is a good way to structure a meeting with your mentee. You can either start with the goal or work logically through the model or you can move the model around, starting with the reality and then the goal, if this works best. Remember to always finish with the way forward and ensure that this is set and owned by the mentee. The model is outlined below.

GROW Model (Manchester Metropolitan University)

Goal – Get the mentee to focus on the future and on what THEY want to achieve as an individual. It is not where you think they should be aiming.

Reality – Ask questions to help the mentee establish where they are now. If you work with the individual directly you may need to give feedback on actual performance. Encourage the individual to get feedback on their performance from their direct line manager if you do not work with them directly as this will help them to identify their current reality.

Options – help the mentee to identify what different options are open to them and ask questions to help them explore the reality of each of these options. Share your own experiences if the mentee is struggling to identify sufficient options and beware of being too directive.

Way Forward – Encourage the mentee to design an action plan which they have set and encourage them to set SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Results-focused, Time-bound) objectives, objectives that are specific, measurable, achievable and realistic for the mentee in their current position and that have clear timescales attached.

SMART stands for:

1. Specific – Objectives should specify what they want to achieve.

2. Measurable – You should be able to measure whether you are meeting the objectives or not.

3. Achievable - Are the objectives you set, achievable and attainable?

4. Realistic – Can you realistically achieve the objectives with the resources you have?

5. Time – When do you want to achieve the set objectives?

3. How individuals learn

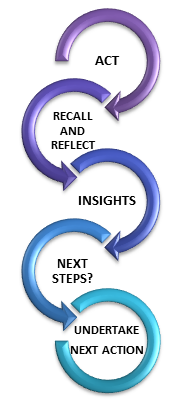

Learning Model (free adaptation from Manchester Metropolitan University)

This diagram shows the process of learning. By following the diagram through we are able as individuals to embed our learning and part of the role of a mentor is to encourage mentees to work through the learning cycle. An individual’s learning style will determine where they will naturally want to spend the most time. For example, activists will want to spend time moving onto new experiences and will have to be encouraged to recall and reflect on experiences they have just been engaged in. Theorists will be reluctant to try out new things until they have all the information they can possibly find. Pragmatists will want to think about and have lots of time to plan how they will approach things. Reflectors will need to be moved on from reviewing what has happened to trying out new experiences.

Understanding the learning style of your mentee is helpful in showing you the part of the learning cycle they will lean towards naturally and where you may need to give a little push. An easy way to find out an individual’s learning style is to ask them to describe something they learned how to do and how they did it. For example, riding a bike, learning a musical instrument, learning a language or how they approach building flat packed furniture. This give you a good indication know about how your mentee likes to learn. It is helpful to also recognise your own learning style so you are aware of the areas you may gloss over as they don’t suit your own natural way of learning.

Understanding the learning style of your mentee is helpful in showing you the part of the learning cycle they will lean towards naturally and where you may need to give a little push. An easy way to find out an individual’s learning style is to ask them to describe something they learned how to do and how they did it. For example, riding a bike, learning a musical instrument, learning a language or how they approach building flat packed furniture. This give you a good indication know about how your mentee likes to learn. It is helpful to also recognise your own learning style so you are aware of the areas you may gloss over as they don’t suit your own natural way of learning.

4. Work with learner to undertake the learning

The Mentor’s role

The relationship between Mentor and Mentee is very much Mentee-centred – focusing on their professional and personal development. It may include the giving of advice, information, establishing facts, sign-posting, self-appraisal, etc. Whatever the techniques, the emphasis is on enabling and empowering the Mentee to take charge of their development and their environment. To allow this transition the importance of interpersonal skills is essential. These skills include listening effectively, empathy, understanding a non-judgemental approach and the ability to facilitate through skilled questioning.

The role of the Mentor is to: listen, question, give information, knowledge about organisation, give advice on career development, offer different perspectives, offer support and encouragement, draw on own experience when appropriate, confront and discuss current issues, take the lead and make decisions in the early stages of the relationship. And to encourage the Mentee to: listen, clarify understanding, share thinking, review and reflect on oneself, change assumptions, consider different perspectives, develop and manage a career plan, take responsibility for their own development, make decisions to maximise the outcomes of the Mentoring relationship.

The Mentee’s role

The Mentee is expected to take ownership and drive the relationship, drawing on the Mentor’s knowledge and experience as required. The Mentee is expected to be open, honest and receiving to enable and empower the Mentor to talk openly and honestly in order to assist the Mentee to take charge of their development and their environment.

Interpersonal skills are essential and include effective verbal communication, listening, questioning and understanding in order to extract and use the required information from the Mentor.

The role of the Mentee is to: communicate their circumstances clearly, concisely and honestly, question where they do not fully understand or comprehend, provide information, knowledge about organisation/occupation and career to aid their Mentor with the provision of advice and support, act upon advice on career development, accept differing perspectives, accept support and encouragement, provide own experience to aid discussions, take the lead, guide and make decisions – when the relationship is established.

The Mentoring relationship

The Mentoring relationship can be a very powerful positive experience. It enables and develops a greater sense of confidence, enhancing the professional and personal skills of both parties. To make sure the experience/relationship is a success, a number of factors need to be addressed.

Factors for success

There are a number of factors which will contribute towards a successful relationship between Mentor and Mentee:

The relationship between Mentor and Mentee is very much Mentee-centred – focusing on their professional and personal development. It may include the giving of advice, information, establishing facts, sign-posting, self-appraisal, etc. Whatever the techniques, the emphasis is on enabling and empowering the Mentee to take charge of their development and their environment. To allow this transition the importance of interpersonal skills is essential. These skills include listening effectively, empathy, understanding a non-judgemental approach and the ability to facilitate through skilled questioning.

The role of the Mentor is to: listen, question, give information, knowledge about organisation, give advice on career development, offer different perspectives, offer support and encouragement, draw on own experience when appropriate, confront and discuss current issues, take the lead and make decisions in the early stages of the relationship. And to encourage the Mentee to: listen, clarify understanding, share thinking, review and reflect on oneself, change assumptions, consider different perspectives, develop and manage a career plan, take responsibility for their own development, make decisions to maximise the outcomes of the Mentoring relationship.

The Mentee’s role

The Mentee is expected to take ownership and drive the relationship, drawing on the Mentor’s knowledge and experience as required. The Mentee is expected to be open, honest and receiving to enable and empower the Mentor to talk openly and honestly in order to assist the Mentee to take charge of their development and their environment.

Interpersonal skills are essential and include effective verbal communication, listening, questioning and understanding in order to extract and use the required information from the Mentor.

The role of the Mentee is to: communicate their circumstances clearly, concisely and honestly, question where they do not fully understand or comprehend, provide information, knowledge about organisation/occupation and career to aid their Mentor with the provision of advice and support, act upon advice on career development, accept differing perspectives, accept support and encouragement, provide own experience to aid discussions, take the lead, guide and make decisions – when the relationship is established.

The Mentoring relationship

The Mentoring relationship can be a very powerful positive experience. It enables and develops a greater sense of confidence, enhancing the professional and personal skills of both parties. To make sure the experience/relationship is a success, a number of factors need to be addressed.

Factors for success

There are a number of factors which will contribute towards a successful relationship between Mentor and Mentee:

- Clear guidelines for the roles and responsibilities of both parties

- Agreed and shared understanding of the nature and type of support

- Commitment towards the principles and values of the Mentoring scheme

- The skills of both the Mentor and Mentee

- Clear communication in both directions

- Clear communication is the cornerstone on which all the other factors sit.

It is through constructive and empathic dialogue the relationship can develop allowing both parties to bring forward their ideas, enter discussions and maintain professional development. It is within this environment both parties can flourish.

5. Ensure that the learner has an adequate support by workplace management and colleagues for learning

Traditionally, mentoring is the long term passing on of support, guidance and advice. In the workplace it has tended to describe a relationship in which a more experienced colleague uses their greater knowledge and understanding of the work or workplace to support the development of a more junior or inexperienced member of staff. It’s also a form of apprenticeship, whereby an inexperienced learner learns the 'tricks of the trade' from an experienced colleague, backed-up as in modern apprenticeship by offsite training.

An important component of the mentoring process is the organization, the atmosphere in which mentoring takes place. It is usually assumed the organization is supportive for a formal mentoring program to exist. This is something that cannot be assumed or left to chance. The organization must be an active participant. The organization is not to enter into the privacy of the mentoring relationship; rather it should develop mentors and mentees through training and education. It should provide the time and resources necessary for the personnel to participate. The organization should, through coordinators and committees, constantly evaluate the processes, be available for intervention, help, and correction.

Not all workplaces or all jobs offer equal opportunities for learning. Perhaps the most important contextual factor related to workplace learning is how work is organised. The traditional Fordist organization represents an extreme form of division of labour: the workers have narrow job descriptions, repetitive tasks, controlled procedures and little opportunities for autonomous decision making. In such work there are few opportunities for learning and development. At the end of the other continuum there are organizations in which work continuously provides new challenges and learning opportunities. In these workplaces workers are rotated between jobs, tasks are carried out by collaborative and self-managed teams with a lot of autonomy, and workers are encouraged to share their expertise and develop their work.

While the organisation of work sets the context and conditions for learning, it continues to be the reciprocal interaction between the individual and the workplace that determines learning. The nature of individuals’ participation in workplace learning depends both on the extent to which the workplace provides opportunities for such participation and on the extent to which individuals choose to avail themselves of those opportunities. Thus, while the workplace creates the possibilities, it is how individuals participate and interact in their workplaces that is central to their leaning. On this view, knowledge is co-constructed through interactions between social practice and the individuals participating in that practice. It is therefore important to acknowledge workplaces as sites for learning.

An expansive work community offers opportunities to take part in many different communities of practice, whereas a restrictive work community limits the opportunities for participation.

Three types of learning opportunity are central to the creation of expansive learning environments:

An important component of the mentoring process is the organization, the atmosphere in which mentoring takes place. It is usually assumed the organization is supportive for a formal mentoring program to exist. This is something that cannot be assumed or left to chance. The organization must be an active participant. The organization is not to enter into the privacy of the mentoring relationship; rather it should develop mentors and mentees through training and education. It should provide the time and resources necessary for the personnel to participate. The organization should, through coordinators and committees, constantly evaluate the processes, be available for intervention, help, and correction.

Not all workplaces or all jobs offer equal opportunities for learning. Perhaps the most important contextual factor related to workplace learning is how work is organised. The traditional Fordist organization represents an extreme form of division of labour: the workers have narrow job descriptions, repetitive tasks, controlled procedures and little opportunities for autonomous decision making. In such work there are few opportunities for learning and development. At the end of the other continuum there are organizations in which work continuously provides new challenges and learning opportunities. In these workplaces workers are rotated between jobs, tasks are carried out by collaborative and self-managed teams with a lot of autonomy, and workers are encouraged to share their expertise and develop their work.

While the organisation of work sets the context and conditions for learning, it continues to be the reciprocal interaction between the individual and the workplace that determines learning. The nature of individuals’ participation in workplace learning depends both on the extent to which the workplace provides opportunities for such participation and on the extent to which individuals choose to avail themselves of those opportunities. Thus, while the workplace creates the possibilities, it is how individuals participate and interact in their workplaces that is central to their leaning. On this view, knowledge is co-constructed through interactions between social practice and the individuals participating in that practice. It is therefore important to acknowledge workplaces as sites for learning.

An expansive work community offers opportunities to take part in many different communities of practice, whereas a restrictive work community limits the opportunities for participation.

Three types of learning opportunity are central to the creation of expansive learning environments:

- the chance to engage in diverse communities of practice in and outside the workplace;

- the organisation of jobs so as to provide employees with opportunities to co-constructing their knowledge and expertise;

- the chance to deal with theoretical knowledge in off-the-job courses (leading to knowledge-based qualifications).

Organisational studies on workplace learning have also emphasised that it is the responsibility of the work organisation to create a propitious climate and other prerequisites for learning by individuals, groups and whole work communities. In other words, space for learning and thinking is needed.

6. Mentoring to support successful work‐based learning programmes

What is Work-Based Learning?

Work-based learning programs provide internships, mentoring, workplace simulations, and apprenticeships along with classroom-based study. In a work-based learning program, classroom instruction is linked to workplace skills through placements outside of the school that allow students to experience first-hand what adults do in jobs.

In the context of career pathways, work-based learning plays a central role in bridging the classroom and the world of work, leading to improved educational and employment outcomes for participants.

Work-based learning helps students contextualize, reinforce, and put into practice their classroom learning while crystalizing their education and career goals and improving their immediate and longer-term employment prospects.

Work-based learning is made of activities that occur in workplaces and that involve an employer assigning a worker or a student meaningful job tasks to develop his or her skills, knowledge, and readiness for work and to support entry or advancement in a particular career field. Work based learning extends into the workplace through on-the-job training, mentoring, and other supports for a continuum of lifelong learning and skill development.

Participants in work-based learning must have opportunities to engage in appropriately complex and relevant tasks (i.e., those that are representative of work in a particular industry, rather than general support roles) aligned with participants’ career goals.

Work-based learning should take place in work environments that support learning by providing appropriate mentoring and supervision. Participants should have opportunities to engage in work-based learning over a sustained period of time in order to ensure that they have adequate opportunity to perform meaningful job tasks.

Such tasks are important because they provide learners with opportunities to develop skills and gain experience relevant to a specific industry, positioning them for successful career entry and advancement.

Role of Mentors for Successful Work-Based Learning W

Workplace mentoring has been identified as an important aspect of work-based learning in projects conducted under the School-to-Work Opportunities Act. By establishing relationships with caring and competent adults who can provide emotional support and facilitate skill development, less-experienced youth and adults are more likely to bridge the gap between school and work. Workplace mentoring requires a partnership commitment that involves time, energy, and resources of qualified mentors, school personnel, and learners themselves. As in other endeavours, workplace mentoring requires planning, training, monitoring, and assessment to ensure that the individuals being mentored will achieve successful outcomes.

Mentors play an influential role in promoting work-based learning and skill development whereby mentees enhance efficiency and productivity at work. The role of mentors has become crucial in facilitating individual learning and skill development. On the other hand, mentoring can help mentors reinforce or, in fact, double their knowledge base. It boosts their self-esteem and gives them increased job satisfaction. Mentoring has benefits for everybody.

Mentors can be effective promoters of workplace learning in that they:

Create a Personalized Learning Environment: Mentors can create an informal setting whereby mentees can feel free to approach them for suggestions. They can understand an individual’s learning styles and the preferences of their mentees and mould the learning process to suit those styles. Thus, they can provide effective guided learning for the best advantage of their mentees.

Facilitate Transition from School to Workplace: Fresher’s come with skills but lack experience in putting those skills to better use in the new environment. Here, mentors can help mentees transform those skills to suit their job responsibilities by timely analysis and guidance.

Provide Emotional and Professional Support: Mentors are out to help mentees in all situations arising in the new workplace. They do everything necessary for the well-being of the mentees. They see that mentees feel comfortable and give of their best. When mentees are sure that there is an experienced colleague looking after them, they can make a focused approach to learn the job skills in a short span of time.

Plan, Monitor and Assess Individual Learning: As in any other pedagogical process, work-based learning too requires planning, monitoring and evaluating individual progress towards the intended outcomes. Mentors play this role to perfection.

Inspire and Throw New Challenges at Mentees: Mentors exude great command of the subject they deal with. Thus, they are not afraid of challenging their mentees who perform below the mark by playing a proactive role as a guide. They behave and act in the best interests of their mentees, thus commanding their respect.

Teach How to Learn in Practice: Out of their experience gained over the years of practice in the field, mentors can give useful anecdotes to their mentees which enable the latter to deal with various difficult situations in the workplace. Thus, they can contribute to confidence-building measures in their mentees.

Work-based learning programs provide internships, mentoring, workplace simulations, and apprenticeships along with classroom-based study. In a work-based learning program, classroom instruction is linked to workplace skills through placements outside of the school that allow students to experience first-hand what adults do in jobs.

In the context of career pathways, work-based learning plays a central role in bridging the classroom and the world of work, leading to improved educational and employment outcomes for participants.

Work-based learning helps students contextualize, reinforce, and put into practice their classroom learning while crystalizing their education and career goals and improving their immediate and longer-term employment prospects.

Work-based learning is made of activities that occur in workplaces and that involve an employer assigning a worker or a student meaningful job tasks to develop his or her skills, knowledge, and readiness for work and to support entry or advancement in a particular career field. Work based learning extends into the workplace through on-the-job training, mentoring, and other supports for a continuum of lifelong learning and skill development.

Participants in work-based learning must have opportunities to engage in appropriately complex and relevant tasks (i.e., those that are representative of work in a particular industry, rather than general support roles) aligned with participants’ career goals.

Work-based learning should take place in work environments that support learning by providing appropriate mentoring and supervision. Participants should have opportunities to engage in work-based learning over a sustained period of time in order to ensure that they have adequate opportunity to perform meaningful job tasks.

Such tasks are important because they provide learners with opportunities to develop skills and gain experience relevant to a specific industry, positioning them for successful career entry and advancement.

Role of Mentors for Successful Work-Based Learning W

Workplace mentoring has been identified as an important aspect of work-based learning in projects conducted under the School-to-Work Opportunities Act. By establishing relationships with caring and competent adults who can provide emotional support and facilitate skill development, less-experienced youth and adults are more likely to bridge the gap between school and work. Workplace mentoring requires a partnership commitment that involves time, energy, and resources of qualified mentors, school personnel, and learners themselves. As in other endeavours, workplace mentoring requires planning, training, monitoring, and assessment to ensure that the individuals being mentored will achieve successful outcomes.

Mentors play an influential role in promoting work-based learning and skill development whereby mentees enhance efficiency and productivity at work. The role of mentors has become crucial in facilitating individual learning and skill development. On the other hand, mentoring can help mentors reinforce or, in fact, double their knowledge base. It boosts their self-esteem and gives them increased job satisfaction. Mentoring has benefits for everybody.

Mentors can be effective promoters of workplace learning in that they:

Create a Personalized Learning Environment: Mentors can create an informal setting whereby mentees can feel free to approach them for suggestions. They can understand an individual’s learning styles and the preferences of their mentees and mould the learning process to suit those styles. Thus, they can provide effective guided learning for the best advantage of their mentees.

Facilitate Transition from School to Workplace: Fresher’s come with skills but lack experience in putting those skills to better use in the new environment. Here, mentors can help mentees transform those skills to suit their job responsibilities by timely analysis and guidance.

Provide Emotional and Professional Support: Mentors are out to help mentees in all situations arising in the new workplace. They do everything necessary for the well-being of the mentees. They see that mentees feel comfortable and give of their best. When mentees are sure that there is an experienced colleague looking after them, they can make a focused approach to learn the job skills in a short span of time.

Plan, Monitor and Assess Individual Learning: As in any other pedagogical process, work-based learning too requires planning, monitoring and evaluating individual progress towards the intended outcomes. Mentors play this role to perfection.

Inspire and Throw New Challenges at Mentees: Mentors exude great command of the subject they deal with. Thus, they are not afraid of challenging their mentees who perform below the mark by playing a proactive role as a guide. They behave and act in the best interests of their mentees, thus commanding their respect.

Teach How to Learn in Practice: Out of their experience gained over the years of practice in the field, mentors can give useful anecdotes to their mentees which enable the latter to deal with various difficult situations in the workplace. Thus, they can contribute to confidence-building measures in their mentees.

7. Conflict during the mentoring process

A positive mentor–mentee relationship is essential for a successful mentoring process.

Mentor should be able dealing with conflict, identify issues and find solutions.

Effective mentors create a supportive environment in which mentors and mentees can:

Mentor should be able dealing with conflict, identify issues and find solutions.

Effective mentors create a supportive environment in which mentors and mentees can:

- express freely and with confidence and trust the source of conflict;

- seek to identify a common goal through compromise;

- remain solution focused:

- manage and evaluate the risks presented by conflict.

Conflicts are a natural result of putting diverse people together and asking them to work as partners. If a mentoring pair can work through conflicts by valuing how diverse they are, the richness of their different viewpoints, background, and experience, then they can learn a great deal more from each other, precisely because they are not thinking the same way. Seen from this perspective, differences can be a strength, not a weakness of any relationship.

Conflict management can be a healthy way to open up lines of communication, initiate problem solving and discuss change. Knowing how to best manage conflict can have many benefits both mentor and mentee. In many cases, conflict in the workplace just seems to be a fact of life. We've all seen situations where different people with different goals and needs have come into conflict. And we've all seen the often-intense personal animosity that can result. The fact that conflict exists, however, is not necessarily a bad thing: as long as it is resolved effectively, it can lead to personal and professional growth. In many cases, effective conflict resolution can make the difference between positive and negative outcomes.

The good news is that by resolving conflict successfully, you can solve many of the problems that it has brought to the surface, as well as getting benefits that you might not at first expect:

Increased understanding: The discussion needed to resolve conflict expands people's awareness of the situation, giving them an insight into how they can achieve their own goals without undermining those of other people.

Increased group cohesion: When conflict is resolved effectively, team members can develop stronger mutual respect and a renewed faith in their ability to work together. Improved self-knowledge: Conflict pushes individuals to examine their goals in close detail, helping them understand the things that are most important to them, sharpening their focus, and enhancing their effectiveness.

However, if conflict is not handled effectively, the results can be damaging. Conflicting goals can quickly turn into personal dislike. Teamwork breaks down. Talent is wasted as people disengage from their work. And it's easy to end up in a vicious downward spiral of negativity and recrimination. If you're to keep your team or organization working effectively, you need to stop this downward spiral as soon as you can.

Conflict management can be a healthy way to open up lines of communication, initiate problem solving and discuss change. Knowing how to best manage conflict can have many benefits both mentor and mentee. In many cases, conflict in the workplace just seems to be a fact of life. We've all seen situations where different people with different goals and needs have come into conflict. And we've all seen the often-intense personal animosity that can result. The fact that conflict exists, however, is not necessarily a bad thing: as long as it is resolved effectively, it can lead to personal and professional growth. In many cases, effective conflict resolution can make the difference between positive and negative outcomes.

The good news is that by resolving conflict successfully, you can solve many of the problems that it has brought to the surface, as well as getting benefits that you might not at first expect:

Increased understanding: The discussion needed to resolve conflict expands people's awareness of the situation, giving them an insight into how they can achieve their own goals without undermining those of other people.

Increased group cohesion: When conflict is resolved effectively, team members can develop stronger mutual respect and a renewed faith in their ability to work together. Improved self-knowledge: Conflict pushes individuals to examine their goals in close detail, helping them understand the things that are most important to them, sharpening their focus, and enhancing their effectiveness.

However, if conflict is not handled effectively, the results can be damaging. Conflicting goals can quickly turn into personal dislike. Teamwork breaks down. Talent is wasted as people disengage from their work. And it's easy to end up in a vicious downward spiral of negativity and recrimination. If you're to keep your team or organization working effectively, you need to stop this downward spiral as soon as you can.

8. Conflict Styles

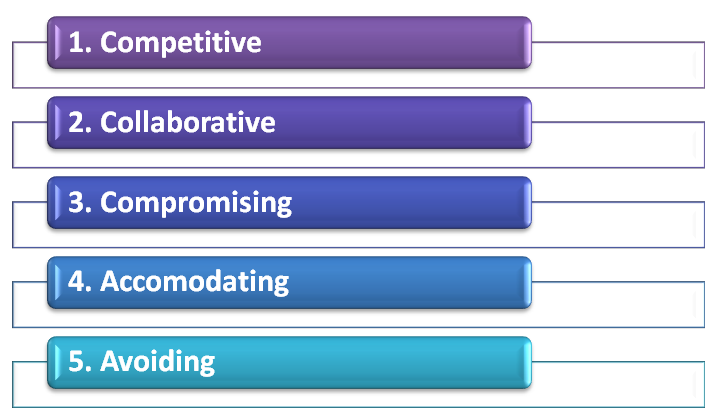

In the 1970s Kenneth Thomas and Ralph Kilmann identified five main styles of dealing with conflict that vary in their degrees of cooperativeness and assertiveness. They argued that people typically have a preferred conflict resolution style. However they also noted that different styles were most useful in different situations. They developed the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) which helps you to identify which style you tend towards when conflict arises. Thomas and Kilmann's styles are:

Conflict styles (free adaptation from Thomas and Kilmann)

1. Competitive: People who tend towards a competitive style take a firm stand, and know what they want. They usually operate from a position of power, drawn from things like position, rank, expertise, or persuasive ability. This style can be useful when there is an emergency and a decision needs to be make fast; when the decision is unpopular; or when defending against someone who is trying to exploit the situation selfishly. However it can leave people feeling bruised, unsatisfied and resentful when used in less urgent situations.

2. Collaborative: People tending towards a collaborative style try to meet the needs of all people involved. These people can be highly assertive but unlike the competitor, they cooperate effectively and acknowledge that everyone is important. This style is useful when a you need to bring together a variety of viewpoints to get the best solution; when there have been previous conflicts in the group; or when the situation is too important for a simple trade-off.

3. Compromising: People who prefer a compromising style try to find a solution that will at least partially satisfy everyone. Everyone is expected to give up something and the compromiser him- or herself also expects to relinquish something. Compromise is useful when the cost of conflict is higher than the cost of losing ground, when equal strength opponents are at a standstill and when there is a deadline looming.

4. Accommodating: This style indicates a willingness to meet the needs of others at the expense of the person's own needs. The accommodator often knows when to give in to others, but can be persuaded to surrender a position even when it is not warranted. This person is not assertive but is highly cooperative. Accommodation is appropriate when the issues matter more to the other party, when peace is more valuable than winning, or when you want to be in a position to collect on this "favour" you gave. However people may not return favours, and overall this approach is unlikely to give the best outcomes.

5. Avoiding: People tending towards this style seek to evade the conflict entirely. This style is typified by delegating controversial decisions, accepting default decisions, and not wanting to hurt anyone's feelings. It can be appropriate when victory is impossible, when the controversy is trivial, or when someone else is in a better position to solve the problem. However in many situations this is a weak and ineffective approach to take.

Once you understand the different styles, you can use them to think about the most appropriate approach (or mixture of approaches) for the situation you're in. You can also think about your own instinctive approach, and learn how you need to change this if necessary. Ideally you can adopt an approach that meets the situation, resolves the problem, respects people's legitimate interests, and mends damaged working relationships.

2. Collaborative: People tending towards a collaborative style try to meet the needs of all people involved. These people can be highly assertive but unlike the competitor, they cooperate effectively and acknowledge that everyone is important. This style is useful when a you need to bring together a variety of viewpoints to get the best solution; when there have been previous conflicts in the group; or when the situation is too important for a simple trade-off.

3. Compromising: People who prefer a compromising style try to find a solution that will at least partially satisfy everyone. Everyone is expected to give up something and the compromiser him- or herself also expects to relinquish something. Compromise is useful when the cost of conflict is higher than the cost of losing ground, when equal strength opponents are at a standstill and when there is a deadline looming.

4. Accommodating: This style indicates a willingness to meet the needs of others at the expense of the person's own needs. The accommodator often knows when to give in to others, but can be persuaded to surrender a position even when it is not warranted. This person is not assertive but is highly cooperative. Accommodation is appropriate when the issues matter more to the other party, when peace is more valuable than winning, or when you want to be in a position to collect on this "favour" you gave. However people may not return favours, and overall this approach is unlikely to give the best outcomes.

5. Avoiding: People tending towards this style seek to evade the conflict entirely. This style is typified by delegating controversial decisions, accepting default decisions, and not wanting to hurt anyone's feelings. It can be appropriate when victory is impossible, when the controversy is trivial, or when someone else is in a better position to solve the problem. However in many situations this is a weak and ineffective approach to take.

Once you understand the different styles, you can use them to think about the most appropriate approach (or mixture of approaches) for the situation you're in. You can also think about your own instinctive approach, and learn how you need to change this if necessary. Ideally you can adopt an approach that meets the situation, resolves the problem, respects people's legitimate interests, and mends damaged working relationships.

9. Conflict resolution theory, methods and models that can be used during the mentoring process

A process to respond to and resolve conflicts should be defined.

We want to introduce the "Interest-Based Relational Approach (IBR)". This type of conflict resolution respects individual differences while helping people avoid becoming too entrenched in a fixed position.

In resolving conflict using this approach, you follow these rules:

Make sure that good relationships are the first priority: As far as possible, make sure that you treat the other calmly and that you try to build mutual respect. Do your best to be courteous to one-another and remain constructive under pressure.

Keep people and problems separate: Recognize that in many cases the other person is not just "being difficult" – real and valid differences can lie behind conflictive positions. By separating the problem from the person, real issues can be debated without damaging working relationships.

Pay attention to the interests that are being presented: By listening carefully you'll most-likely understand why the person is adopting his or her position.

Listen first; talk second: To solve a problem effectively you have to understand where the other person is coming from before defending your own position.

Set out the "Facts": Agree and establish the objective, observable elements that will have an impact on the decision.

Explore options together: Be open to the idea that a third position may exist, and that you can get to this idea jointly.

By following these rules, you can often keep contentious discussions positive and constructive. This helps to prevent the antagonism and dislike which so-often causes conflict to spin out of control.

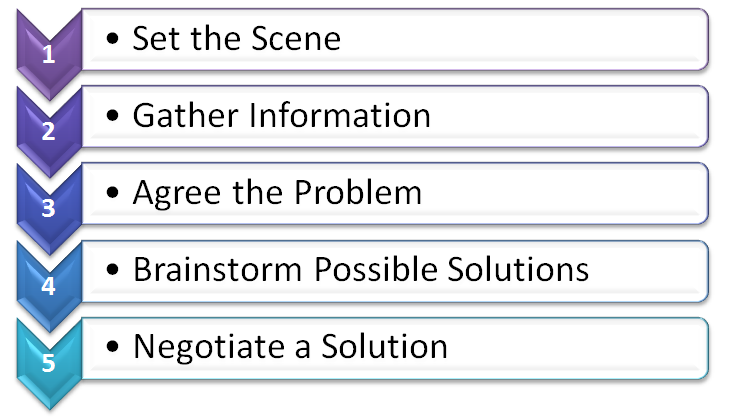

A Conflict Resolution Process

Based on this approach, a starting point for dealing with conflict is to identify the overriding conflict style employed by yourself, your team or your organization. Over time, people's conflict management styles tend to mesh, and a "right" way to solve conflict emerges. It's good to recognize when this style can be used effectively, however make sure that people understand that different styles may suit different situations. Look at the circumstances, and think about the style that may be appropriate. Then use the process below to resolve the conflict:

We want to introduce the "Interest-Based Relational Approach (IBR)". This type of conflict resolution respects individual differences while helping people avoid becoming too entrenched in a fixed position.

In resolving conflict using this approach, you follow these rules:

Make sure that good relationships are the first priority: As far as possible, make sure that you treat the other calmly and that you try to build mutual respect. Do your best to be courteous to one-another and remain constructive under pressure.

Keep people and problems separate: Recognize that in many cases the other person is not just "being difficult" – real and valid differences can lie behind conflictive positions. By separating the problem from the person, real issues can be debated without damaging working relationships.

Pay attention to the interests that are being presented: By listening carefully you'll most-likely understand why the person is adopting his or her position.

Listen first; talk second: To solve a problem effectively you have to understand where the other person is coming from before defending your own position.

Set out the "Facts": Agree and establish the objective, observable elements that will have an impact on the decision.

Explore options together: Be open to the idea that a third position may exist, and that you can get to this idea jointly.

By following these rules, you can often keep contentious discussions positive and constructive. This helps to prevent the antagonism and dislike which so-often causes conflict to spin out of control.

A Conflict Resolution Process

Based on this approach, a starting point for dealing with conflict is to identify the overriding conflict style employed by yourself, your team or your organization. Over time, people's conflict management styles tend to mesh, and a "right" way to solve conflict emerges. It's good to recognize when this style can be used effectively, however make sure that people understand that different styles may suit different situations. Look at the circumstances, and think about the style that may be appropriate. Then use the process below to resolve the conflict:

Conflict resolution process (free adaptation of IBR Approach)

Step One: Set the Scene

If appropriate to the situation, agree the rules of the IBR Approach (or at least consider using the approach yourself.) Make sure that people understand that the conflict may be a mutual problem, which may be best resolved through discussion and negotiation rather than through raw aggression. If you are involved in the conflict, emphasize the fact that you are presenting your perception of the problem. Use active listening skills to ensure you hear and understand other's positions and perceptions.

Three guiding principles (free elaboration)

Key Points

Conflict in the workplace can be incredibly destructive to good teamwork. Managed in the wrong way, real and legitimate differences between people can quickly spiral out of control, resulting in situations where co-operation breaks down and the team's mission is threatened. This is particularly the case where the wrong approaches to conflict resolution are used. To calm these situations down, it helps to take a positive approach to conflict resolution, where discussion is courteous and non-confrontational, and the focus is on issues rather than on individuals. If this is done, then, as long as people listen carefully and explore facts, issues and possible solutions properly, conflict can often be resolved effectively.

Step One: Set the Scene

If appropriate to the situation, agree the rules of the IBR Approach (or at least consider using the approach yourself.) Make sure that people understand that the conflict may be a mutual problem, which may be best resolved through discussion and negotiation rather than through raw aggression. If you are involved in the conflict, emphasize the fact that you are presenting your perception of the problem. Use active listening skills to ensure you hear and understand other's positions and perceptions.

- Restate.

- Paraphrase.

- Summarize.

- And make sure that when you talk, you're using an adult, assertive approach rather than a submissive or aggressive style.

Step Two: Gather Information

Here you are trying to get to the underlying interests, needs, and concerns. Ask for the other person's viewpoint and confirm that you respect his or her opinion and need his or her cooperation to solve the problem. Try to understand his or her motivations and goals, and see how your actions may be affecting these. Also, try to understand the conflict in objective terms: Is it affecting work performance? Damaging the delivery to the client? Disrupting team work? Hampering decision-making? Or so on. Be sure to focus on work issues and leave personalities out of the discussion.

Here you are trying to get to the underlying interests, needs, and concerns. Ask for the other person's viewpoint and confirm that you respect his or her opinion and need his or her cooperation to solve the problem. Try to understand his or her motivations and goals, and see how your actions may be affecting these. Also, try to understand the conflict in objective terms: Is it affecting work performance? Damaging the delivery to the client? Disrupting team work? Hampering decision-making? Or so on. Be sure to focus on work issues and leave personalities out of the discussion.

- Listen with empathy and see the conflict from the other person's point of view.

- Identify issues clearly and concisely.

- Use "I" statements.

- Remain flexible.

- Clarify feelings.

Step Three: Agree the Problem

This sounds like an obvious step, but often different underlying needs, interests and goals can cause people to perceive problems very differently. You'll need to agree the problems that you are trying to solve before you'll find a mutually acceptable solution. Sometimes different people will see different but interlocking problems – if you can't reach a common perception of the problem, then at the very least, you need to understand what the other person sees as the problem.

Step Four: Brainstorm Possible Solutions

If everyone is going to feel satisfied with the resolution, it will help if everyone has had fair input in generating solutions. Brainstorm possible solutions, and be open to all ideas, including ones you never considered before.

Step Five: Negotiate a Solution By this stage, the conflict may be resolved: Both sides may better understand the position of the other, and a mutually satisfactory solution may be clear to all. However you may also have uncovered real differences between your positions. This is where a technique like win-win negotiation can be useful to find a solution that, at least to some extent, satisfies everyone.

There are three guiding principles here: Be Calm, Be Patient and Have Respect.

This sounds like an obvious step, but often different underlying needs, interests and goals can cause people to perceive problems very differently. You'll need to agree the problems that you are trying to solve before you'll find a mutually acceptable solution. Sometimes different people will see different but interlocking problems – if you can't reach a common perception of the problem, then at the very least, you need to understand what the other person sees as the problem.

Step Four: Brainstorm Possible Solutions

If everyone is going to feel satisfied with the resolution, it will help if everyone has had fair input in generating solutions. Brainstorm possible solutions, and be open to all ideas, including ones you never considered before.

Step Five: Negotiate a Solution By this stage, the conflict may be resolved: Both sides may better understand the position of the other, and a mutually satisfactory solution may be clear to all. However you may also have uncovered real differences between your positions. This is where a technique like win-win negotiation can be useful to find a solution that, at least to some extent, satisfies everyone.

There are three guiding principles here: Be Calm, Be Patient and Have Respect.

Three guiding principles (free elaboration)

Key Points

Conflict in the workplace can be incredibly destructive to good teamwork. Managed in the wrong way, real and legitimate differences between people can quickly spiral out of control, resulting in situations where co-operation breaks down and the team's mission is threatened. This is particularly the case where the wrong approaches to conflict resolution are used. To calm these situations down, it helps to take a positive approach to conflict resolution, where discussion is courteous and non-confrontational, and the focus is on issues rather than on individuals. If this is done, then, as long as people listen carefully and explore facts, issues and possible solutions properly, conflict can often be resolved effectively.

10. Bibliography

- Mentoring Guidelines, Human Resources Organisational Development Training and Diversity, Manchester Metropolitan University https://www2.mmu.ac.uk/media/mmuacuk/content/documents/human-resources/a-z/guidance-procedures-and-handbooks/Mentoring_Guidlines.pdf

- CIPD - Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (London) West Yorkshire CIPD, Branch Mentoring Programme https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/west-yorkshire-mentoring-pack_2011_tcm18-9423.pdf

- Lonnie D. Inzer and C. B. Crawford, A Review of Formal and Informal Mentoring: Processes, Problems, and Design, article on Journal of Leadership Education Volume 4, Issue 1 - Summer 2005 http://www.journalofleadershiped.org/attachments/article/137/JOLE_4_1_Inzer_Crawford.pdf

- Tynjala, Paivi, Perspectives into Learning at the Workplace, article on Educational Research Review, v3 n2 p130-154 2008 https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ813067 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1747938X0800002X?via%3Dihubhttps://www.scribd.com/document/310807723/Werkplekleren-Educational-Research-Review

- Cahill C., Making Work-based Learning Work. Jobs for the Future (July 2016) http://www.jff.org/sites/default/files/publications/materials/WBL%20Principles%20Paper%20062416.pdf

- https://blog.commlabindia.com/elearning-design/role-of-mentor

- Al-Tabtabai, H. M., Alex, A. P., & Abou-alfotouh, A. (2001). Conflict resolution using cognitive analysis approach: a quantitative approach. Project Management Journal, 32(2), 4–16. https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/conflict-resolution-using-cognitive-analysis-approach-1997

- http://starscomputingcorps.org/team-dynamics-student-module-conflict-management-and-resolution-0